我们的40周年纪念书讲述了SRK于1974年成立以及随后发展成为资源行业最受尊敬的咨询公司之一的经历。

除了描述我们在世界各地发展的办事处,这本书提供了对我们所持理念的见解和SRK的独特之处。许多员工轶事证明了我们公司成功的主要原因:员工的奉献。

您可以下载以下书目的所有章节。为了优化浏览,我们建议Mac设备使用Apple Books,Windows设备使用Caliber。

Oskar Steffen, Andrew MacGregor Robertson and Hendrik Kirsten in the mid-1970s were three very different men who shared a common ambition and desire. Though separated only by a few years in age, they had different personalities and enjoyed different areas of professional expertise — the first was a leading specialist in the great gaping maws of open-pit mining, the second a master of soils and foundations, and the third an expert in the structural stresses and extraordinary pressures of rock mechanics.

Steffen, Robertson and Kirsten began their working partnership with each man already fairly busy — they moved what they were doing on their own into a shared environment and planned to grow as a result of synergy. Each brought clients into the partnership. Although the success of a specialised geotechnical services firm might not be assured, the men and their expertise were in demand from the moment they set up shop.

Andy Robertson arrived in Vancouver in August 1977, the same month that Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon, opened the Lookout Restaurant atop Harbour Centre, the city’s tallest building at 147 metres. Dubbed “the little village on the edge of the rainforest,” Vancouver, and Canada’s West Coast, was a far different place than conservative, racially divided Johannesburg. It was liberal writ large, Canada’s California, home to a healthy counterculture and a frontier’s entrepreneurial, caveat emptor ethics. Robertson’s marketing enthusiasm and ambition made the city the perfect place for him to make a landing.

SRK was on the verge of a boom in South Africa when Andy Robertson departed for North America in August 1977. Over the following decade, it greatly expanded the range of services being offered, which was why it was able to support its sister operation in North America during the 1982 downturn. In spite of the worsening racial tensions, the firm grew across the country, and its increasingly solid reputation brought international work. It created a bankable brand in civil engineering as well as mining, with landmark projects and the widening scope of its work

Recovering from the 1982 recession and rebuilding the North American business proved more difficult than Andy Robertson had expected. The handful of people in the Denver office had survived the slump without too much difficulty, thanks to the solid projects they already had on the go. In fact, the Denver office grew from 13 to 18 in 1982–1984. Ian Hutchison continued to develop the water practice and John Welsh’s geotechnical section provided the bulk of the work, primarily the Thompson Creek tailings project. During his regular visits from Vancouver, Robertson was involved at an executive level — working on tenders or contract bids, reviewing major projects, recruiting staff, keeping track of the financials. Everyone was fairly independent in terms of pursuing clients and projects.

In early 1981, Neal Rigby found himself tossing and turning, unable to sleep. The increasing tension in South Africa coupled with the distance from supportive relatives was proving too difficult for his family. His wife wanted to return to the U.K. Rigby feared it spelled the end of the best job he had ever had. He loved working for SRK, and he didn’t know how he was going to tell Dick Stacey, his boss and mentor for three and a half years, that he was leaving.

The growth of SRK throughout the 1980s, and the organisational change that produced, sparked a self-conscious discussion within the company about its values, its core business and its culture. More and more partners came to agree that the group share structure and worldwide network of corporate entities that had developed over the years needed to be rationalised. The entire group was in want of better order in the same way as the South African unit had needed restructuring. It was also clear that the founders and first generation of the company needed an exit strategy, which was complicated given the turmoil in South Africa and the size of their shareholding.

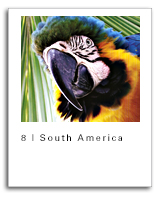

In May 1985, Dennis Laubscher, a crusty geologist who joined SRK from Zimbabwe as a leading expert in block-cave mining, had a telephone call from Fluor Daniel in South America. The Chilean state-owned mining corporation, Codelco (Corporación Nacional del Cobre de Chile, the national copper corporation of Chile), wanted him to look at the Andina Mine, about 50 kilometres northeast of Santiago. He was soon on a plane to South America.

By the late 1980s, Australia was the world’s third-ranking mining country — the largest producer of aluminum and lead, second-largest of iron ore and zinc, fifth in coal, eighth in copper. More importantly, changes in gold processing technology meant that a massive increase in gold production was also underway. With demand for specialist services on the increase and more and more clients offering work Down Under, SRK wanted to be a part of the action.At the same time, civil unrest in South Africa was taking an increasing toll on SRK SA. Many of those who wanted to leave weren’t interested in moving to the U.K. Brian Wrench was one.

In addition to the SRK Group’s reasons for reforming the way North America was doing business in the 1990s, the internal North American corporate dynamics required attention. What was a top-down model had to be transformed into a partnership model, where a broader range of senior staff participated in decisions. But that desire to better reflect the values of the group and put power into the hands of those who made it work could triumph only as an evolution and not a revolution. Allowing time for the change to happen organically rather than imposing it was critical. As a result, the SRK Group in the final years of the 20th century and the first few years of the 21st spent significant time making sure it got the transition to an international consultancy right.

In the wake of the end of the British Coal deal at the end of 1994, SRK UK initially scrambled for work. The number of people ebbed to some 25 full-time staff as the consultants from other SRK offices and contract personnel left. Surprisingly little work came SRK UK’s way from the privatised coal industry.

In 1990, SRK began planning to leave downtown Johannesburg. Security, as much as space, was becoming an increasing concern. In April 1991, the Johannesburg offices moved into 265 Oxford Road, Illovo. More than 180 employees of SRK and Gemcom were involved, bringing to fruition months of extensive consultations, planning and effort. The purpose-designed 3,000-square-metre office block was set in garden-like surroundings. By 1997 it was too small, and another 1,600 square metres were added.

Work waltzed in the door for SRK as depressed commodity prices recovered in the opening years of the new millennium. The competition turned out to be not for contracts but for people — experienced, qualified staff. There weren’t enough, especially in the swath of developing nations where mining development was again proceeding at a breakneck pace. The company disliked establishing shop-window offices in new countries; storefront façades to attract clients who were then serviced by consultants parachuted in to complete the work. It preferred to work along with and ultimately depend on local talent.

On the eve of its 40th anniversary, SRK had matured into a global group with more than 50 permanent offices in 23 countries on 6 continents. It boasts more than 1,500 scientists, geologists, engineers, specialists, managers and support staff — experts in exploration, resource evaluation, due diligence, geotechnical services, water, environmental management, project evaluation, tailings, waste, extractive metallurgy and mineral processing. It is a multi-specialist consultancy, owned by the staff, with the long list of internal shareholders produced as an appendix in each annual report.