Session: MINING & EXPLORATION: GEOSCIENCES: OPEN PIT GEOTECHNICAL: STRATEGIES FOR DESIGN & OPERATION | Room 255F

A greenfield gold project in Latin America was in the planning phase in the late 1990s. Approximately 15 million tonnes of waste rock would be moved to access approximately 11 million tonnes of leach ore. Construction started in late 2003 and the open pit gold mine began operations about 1 year later. Three years into production, the operations team observed cracks around the waste rock dump and the footprint of the uphill heap expansion. Nine months later, a geotechnical consultant acknowledged the potential for a deep-seated landslide below the waste rock and heap leach facilities. In response, the operator suspended operations and commenced rinsing of the leach pad to reduce cyanide levels. Less than 3 months later, the predicted deep-seated landslide occurred. Engineers estimated approximately 35 million cubic meters of mass movement below the waste rock and heap leach facilities.

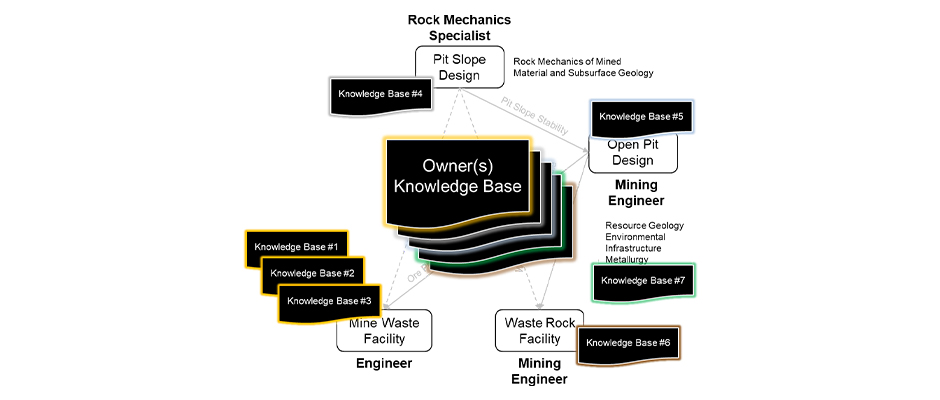

Approximately 2 years after a geotechnical failure that resulted in the shutdown of the newly opened gold mine, the owner filed a Statement of Claim and named three engineering design firms and individuals involved in the project. The basis for litigation was an owner’s project file that was adequate to start the lawsuit. For the next several years, the defendants and owner moved through a legal process of data discovery and expansion of the technical documentation relevant to the case. The responsibility for improving the knowledge base laid with the defendants. As this paper explains, custody of the various project documents varied over the course of transitions in the owner’s team, changes in the external consulting teams and a hiatus during the project development period. None of these transitions or changes were unique to a mining project development. The additional time required by the defendants to re-construct a meaningful technical knowledge base long after the fact was substantial. A better, integrated knowledge base may not have prevented the failure; however, the project team would have been better positioned to communicate risk and identify risk mitigation strategies.

Click here to register!

Click here to view all presentations at this event.