The regulation of the operation of mines in countries of the Former Soviet Union (FSU) generally follows the scheme established during the mid-20th century, with updates and amendments periodically made to maintain contemporary relevance. The mining industry in Central Asia is modernizing at a rate that is prone to out-pacing the ability of the legislation to change.

SRK’s Moscow Team was recently commissioned by a client in Kazakhstan to support efforts to improve the performance and efficiency at its open pit and underground mines. SRK was requested to advise the client on global modern practices and regulations, and to prepare documentation as part of the client’s process of seeking exemption from certain regulations.

The client determined that certain conditions of the federal legislation governing the design and operation of mines were constraining the performance of the mines, and that relief from the conditions would give significant operational and economic benefits. The client asked SRK to report comparable standards from around the globe and to provide documentation in support of the client’s negotiations with the regulators.

The client sought relaxation from the following regulations:

Open pit

- The maximum gradient of a transport ramp in an open pit mine is limited to 8%.

- In lengths of open pit ramp (+600 m, =>6% gradient), a flat section (2% gradient) at least 50 m long must be incorporated, breaking the ramp into <600 m long flat sections.

Underground

- Ventilating air requirement for diesel engines of 5 m3/min/hp (equal to 0.112 m3/sec/kW).

- The maximum speed for hoisting materials in a vertical shaft of 12 m/s.

SRK Moscow collaborated with specialists in a number of its international offices to understand their local regulations and to identify risk management initiatives that were being used to satisfy both the regulations and safe operations. Advice was received from SRK specialists in Santiago (Chile), Denver (USA), Vancouver and Sudbury (Canada), Perth (Australia), and Astana (Kazakhstan) offices and the broad conclusions are discussed below.

Approach to Mine Safety

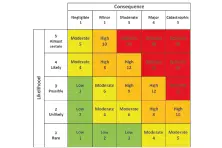

In most global, non-FSU jurisdictions, the approach to regulating mining safety has changed from a prescriptive system pre-2000, to an outcomes based, risk management approach with self-determined methods of achieving an acceptable level of risk. The mining regulations provide outcomes which must be achieved through the mine operator’s management practices. The Hierarchy of Controls shown in Figure 1 provides guidance for prioritizing intended practices and the Risk Evaluation Matrix ( Figure 2 below) is used to evaluate the effectiveness of the initiatives.

Open pit

- FSU jurisdictions retain similar regulations to those in Kazakhstan for conditions which were established before the development of modern equipment with advanced braking and cooling systems. None of the non-FSU jurisdictions reviewed had legislation limiting the haul road gradients or requiring flat sections to be incorporated into ramps.

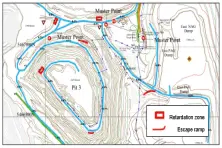

Some non-FSU countries have requirements for run-away management facilities (Figure 3) to be installed, although the format of these facilities is not prescribed. Some jurisdictions require the creation of a formal Code of Practice to define the risk management practices and installation of initiatives such as inclined escape ramps and centerline arrestor berms (Figure 4).

Underground

- For ventilating underground mines, all jurisdictions have specifications for the quality of air in working places, in terms of temperature, minimum content of oxygen, and maximum content of contaminants including the products of combustion. Most jurisdictions prescribe the minimum quantity of air to be supplied based on engine power, as in Kazakhstan. Some jurisdictions only refer to the requirement to achieve specified standards for air in the work place, which is the outcomes based approach. Regardless, a Risk Management approach is required to ensure the implemented controls are adequate. It was noted that the quantity of ventilating air required by the Kazakhstan regulations is similar to that of a number of other countries, a standard that was developed during the mid-20th century as the use of diesel engines underground rapidly increased. This standard is now about twice that of the lowest regulated standards, which have been adapted to modern low emission equipment operating with low sulphur content diesel fuel.

- Hoisting speeds are regulated in most jurisdictions through the more frequent practice of specifying maximum limits to acceleration and deceleration, rather than absolute limits to speed. The limitations to acceleration control the dynamic forces experienced by the shaft conveyances and their contents (including passengers), attachments, ropes and winding equipment during hoisting cycles, therefore the maximum possible speed in a shaft can be determined by the hoisting distances, meaning that conveyances in shallower shafts will not be able to attain the speeds of conveyances in deeper shafts. As a result, a maximum hoisting speed of 16 m/s is not unusual in deep mines, with hoisting speeds exceeding that in some very deep mines. Operators are expected to undertake assessments of the hoisting equipment and shaft to confirm it is capable of running at the selected acceleration rates.

SRK demonstrated that many jurisdictions have adopted the risk management approach to the regulation of mine safety and that practical solutions have been developed to ensure operations can proceed efficiently without the need for the prescriptive standards. Having presented the client with data from various sources to support the contention that operations can be undertaken safely without the prescriptive regulations, SRK’s client is now in discussions with government and local design institutes to gain formal approval for relaxation of some of the prescriptive standards of the regulations in question.