Protecting the environment and communities in and around exploration and mining projects is now a major issue in valuing mineral assets, with the media and society at large elevating the need for a ‘social license’ to mine into daily conversations and even protests.

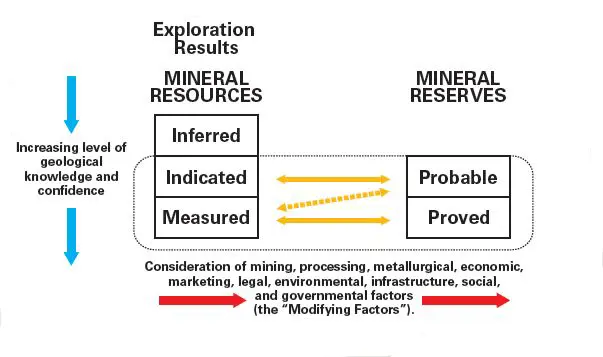

The major reporting codes have recently recognised the importance of these issues, by adding ‘infrastructure’ and ‘social’ as additional modifying factors to be considered when converting a mineral resource to a mineral reserve (Figure 1).

The question posed recently – and the question for the project valuator – is how to measure the impact or cost of obtaining a social licence to mine on the financial feasibility of a project.

Previously, if applying for an exploration or mining permit, a reasonable expectation that the relevant government departments would issue it would be sufficient (community engagement and social and labour plans are required before applying).

However, in today’s world, government is not the only constituent to be considered. All interested and affected parties have to be engaged and they have to issue the social licence. To further complicate matters, this is not a one-off exercise; the social licence has to be obtained and maintained throughout all the phases of a mining project from early exploration to mine closure.

My first response to the question was that a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary risk assessment should be undertaken in all phases of a project – which recognises all the risks to the project and attaches some quantitative judgment to them.

While mitigating actions to ameliorate the risk profile should be managed on an ongoing basis, the valuator has to value the project at a particular point in time. There are levels of risk in all aspects of a project which can be estimated and a risk factor built into financial calculations.

However, the risks associated with environmental and social matters do not lend themselves to a mechanistic calculation; rather, they tend to be more qualitative in nature. The risk continuum ranges from project termination at the one end, to a sustainable mining operation where all stakeholders realise value from the project, at the other. This does not mean that the risks are any less serious. For instance, it would be interesting to know what risk was attached to social aspects in the case of the Pascua-Lama project on the border of Chile and Argentina – which has been stopped indefinitely under a court order on a matter concerning the water supply to local communities.

To consider all risks associated with a mining project, there is a need to apply a multi-disciplined team approach to mineral asset valuation; this is what SRK supports with its broad spectrum of skills and disciplines across the world.