We begin where all mining geoscience-focused newsletters should, with obscure

American Civil War naval history. It is 1864, and a flotilla of Union ships sail towards the Confederate port of Mobile Bay, Alabama.

One Union warship has already been sunk by a Confederate line of underwater mines (called torpedoes in the 1860s) when Union Rear Admiral David G. Farragut gave his ships the now-famous order of: ‘Damn the torpedoes! Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!’.

Miraculously, the rest of Farragut’s fleet sail unharmed through the minefield, enabling them to get beyond the range of the shore-based guns and ultimately take control of Mobile Bay. The capture of the Bay severed Confederate supply lines at one of their last major ports and served as a major factor in ending the war. The idiom ‘Damn the torpedoes!’ stands now as a famous reference to advancing to success despite the apparent risk.

What Farragut didn’t know was that most of the mines at the entrance to the bay had become waterlogged since the first Union ship was destroyed and simply failed to detonate as his ships pushed them out of the way. Had the mines been operational, it would have spelled disaster for his ships, for the Union war effort, and potentially changed the course of history. Of course, Farragut’s well-known quote would be famous for a very different reason.

The relationship between an obscure history reference and mineral resource

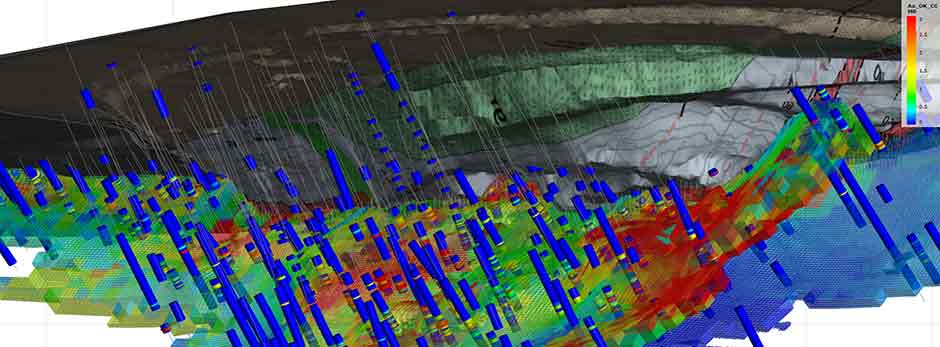

estimation may not be immediately obvious. Like Admiral Farragut, mining companies face numerous and substantial risks to achieve success throughout their project development cycle, often beginning with the mineral resource estimate. Estimation implies inherent risk in the certainty of the result, yet this is often glossed over to provide assurance to investors or internal stakeholders of a stable foundation on which to base a myriad of expensive downstream decisions. Risks are also understood only in the context of conditions or assumptions as we understand them, and those commonly change with time. Like the changing conditions in the Battle of Mobile Bay, our perspective on risk in a geological model or mineral resource estimate may fluctuate as new information is generated or as market conditions change. It is often understood by geoscientists that we sample a very small part of the thing we are trying to characterise, and what happens between points of observation is uncertain on a sliding scale of geological complexity. Despite our best efforts, mining investment or project development often takes the ‘damn the torpedoes’ approach regardless of uncertainty. As a result, the concept of ‘no risk, no reward’ is generally understood for any investor in commodities or mining.

This approach doesn’t absolve the modern geoscientist of a responsibility to do good work, assign relative confidence in the result, and be able to relay these concepts to stakeholders at all levels. Significant investment decisions get made on the basis of resource estimations, and bad decisions can quickly (and publicly) turn into significant losses. When the estimate shifts or changes due to new information, interpretation, economics, constraints, or dozens of other factors, it is not uncommon for reactions to be surprise, disappointment, or even anger.

Although uncommon, the failure of a large mining project due to significant issues in mineral resource estimation could hurt the wellbeing of countless stakeholders - from company executives and institutional investors to rank-and-file employees, mom-and-pop shareholders and local communities that supported the project. Therefore, it is critical that the risks associated with these estimations be clearly communicated to decisionmakers and stakeholders beforehand.

There are multiple factors which inhibit this communication. Every ore deposit is different, and each features challenges or uncertainties which may be unique or

difficult to model or quantify effectively. There are multiple mechanisms for reporting of mineral resource estimates, none are authoritative, and all leave ultimate decision making on confidence and risk to the subjective opinion of a person. In many cases, this person is designated as qualified or competent, although the definitions of this are highly variable. Internal and external governance of resource (and reserve) estimation process is inconsistent in terms of rigour, timing, or impacts to public statements. Technical reports are generally the final source of information for investors to understand the project, but are commonly too long and complex for the layman to interpret efficiently. Mistakes or omissions are common in technical reports as well, with a very small percentage of these types of disclosure reviewed by regulatory agents. They are often pulled together immediately before filing deadlines, in many cases from multiple sources.

Given the complexity of these documents and murkiness of the language, it is no surprise that modern investors often skip through ponderous technical reports and go straight to a table showing tonnes and grade, net present values, or rates of return. The absence of a concise summation of the risks in mineral resource estimation also makes investors more susceptible to the sorts of language that can appear in press releases, such as ‘bonanza’, ‘world-class’ and ‘open in all directions’. People naturally gravitate to information that is simple, and even more so if it is simply sensational.

We can (and should) argue that mining projects are complicated and require appropriate governance, review and documentation to support business decisions. But it is up to geoscientists in the modern mining industry to adapt and do all of this better and more efficiently by applying the lessons of the past to the concepts and tools of the future. Whether we like it or not, we find ourselves in a world where complex situations or major events are often delivered in real time, with very little background, in fewer than 280 characters. The technical report isn’tgoing away, but the approach to any form of disclosure or documentation should recognise the audience and present relevant information in a concise and clear fashion. Risks and opportunities should be front and centre and worded with as little equivocation as possible. Governance should be rigorous, but streamlined to best fit the project. Modern geoscientists should also look beyond the written report and develop other innovative ways to convey information or concepts to stakeholders.

It is my hope that the contributions in this edition of SRK News will touch on a variety of ways for consultants and their clients to evaluate and communicate risks (and opportunities) in mineral resource estimation.